Our Story

There’s a property on Mackey Street, right in the heart of what is now the eastern part of the city, where fruit still grows, chickens roost, and cockatoos and macaws and night owls congregate. It’s got trees and breeze and a shaded park that drops delicate poui blossoms in season.

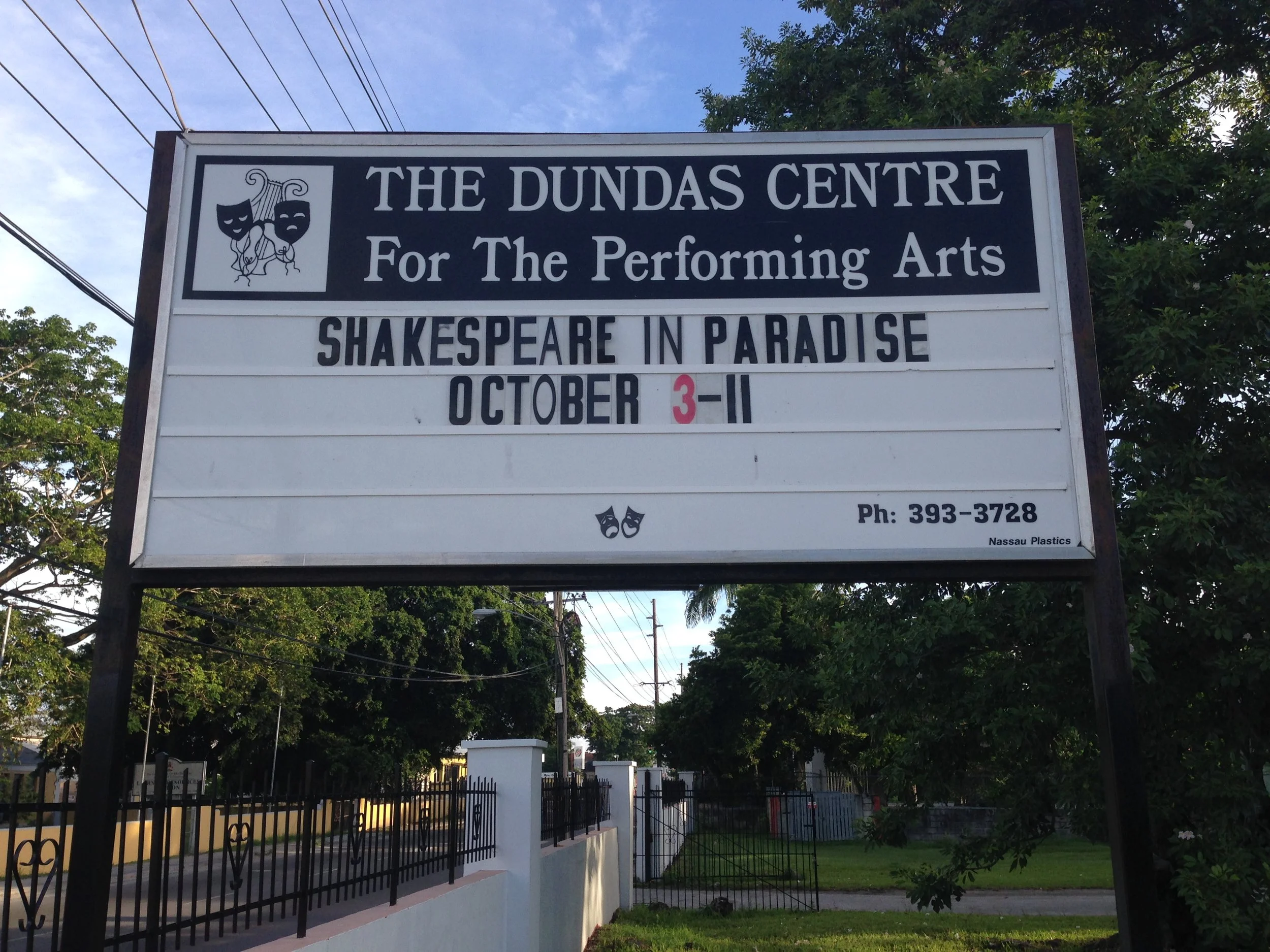

It’s the Dundas.

This place, which is now a centre for the performing arts, has a history that is complicated and unique and thoroughly misunderstood. So we thought we’d fill you in on that history and explain a little about its current mission, vision, and leadership.

Cast your minds back to 1929. A category 4 or 5 hurricane—no one’s too sure exactly which, as the methods of measuring back then were not as they are today—has just ravaged the city of Nassau. It’s still the worst hurricane to hit the capital, and the destruction and misery in its wake were severe.

The wife of the then governor, Sir Charles Dundas, establishes with some other upstanding citizens a civic association designed to alleviate some of that suffering by offering training and job placement for many of the people in the hard-hit Over-the-Hill area. So in 1931 the Dundas Civic Centre was born.

For the first part of its existence, it operated out of what is now Woodcock Primary School on Hospital Lane. But as it grew it needed a new location, and the land on Mackey Street was set aside for that purpose. In time, the building that is now called the Winston V. Saunders Theatre was built. It was built, as people who go there will see, to last; to withstand other hurricanes; with buttressed walls and a high, high ceiling, and a floor that was raised enough to ride above floodwaters.

In 1940, the Dundas Civic Centre was incorporated as a not-for-profit company and left in trust for the Bahamian people. For the first ten years of its official existence, it continued to offer training and job placement for domestic servants. But during the 1950s the demand for that kind of training and employment was tapering off, and the building was falling into disuse.

It so happened, though, that it was an excellent design for theatre. So amateur theatre groups began occupying the premises. There was some overlap between their membership and the early directors of the company, who were people like Ralph Collins (who built the wall and after whom Collins Avenue is named), H. G. Christie, and Harry P. Sands, and so the transition from training centre to theatre was seamless. When the Nassau Amateur Operatic Society and the Nassau Music Festival were established in the 1950s, both found an early home at the Dundas.

In 1960, the transformation from training centre to theatre was cemented when Meta Davis Cumberbatch, grandmother of the Maynard clan, commissioned the building of the stage. The stage and the lighting booth were added, but seating remained transitory. As the 1960s progressed, more and more people began occupying the Dundas, using it for performances. Groups like the Nassau Players, the Bahama Drama Circle, the University Players and others began to offer shows there. By the end of the 1960s, with majority rule accomplished and independence round the corner, it was clear that Nassau needed a theatre more than it needed a training school for domestic servants.

So around that time, it was determined that the directorship of the Dundas company should change to reflect its evolving purpose. Instead of comprising real estate magnates, politicians, Bay Street businessmen and lawyers, the board of directors was turned over to the theatre people themselves. In 1970, the memorandum of association was revised to update the purpose and the directorship of the centre. Added to the purposes of the company was the intention “to encourage and assist in the development of all forms of cultural activity in the Commonwealth of the Bahamas”, and the articles were changed so that the actual members of the company were between five and nine not-for-profit performing arts associations. These groups governed the Dundas for fifty years.

In all this time, the Dundas was a private not-for-profit company set up in trust for the Bahamian people.

In all this time, the Dundas received no support from the government. Specific productions might find grants and investors, but it raised its funds from the revenue it generated from performances and rentals. It also received very limited support from corporate Bahamas.

In all this time, too, the Dundas employed very little staff. None of the actors were paid. None of the producers were paid. Rewards were intangible and in kind: cast bars, cast parties, DANSA awards. No salaries.

The manager was paid a meagre part-time salary; show directors worked for 50% of the net.

A caretaker lived on property, and the majority of his compensation was to live rent-free and with all utilities paid for.

The Dundas, by and large, was a voluntary organization, and in that way it was a success.

II.

But a lot happens in fifty years.

One by one, the groups who constituted the Dundas Board ceased operation and closed. The theatre itself was transformed from a hall in which concerts, lectures and performances were given on occasion into a working community theatre, which ran a repertory season, presented visiting performances, and became the home of annual performing arts festivals, and which cemented the reputation of local playwrights and performers. It created folk operas, grand operas, high tragedy, low comedy, and presented concerts, circuses, acrobats, and dance troupes. It served as the locale for school and church performances, a place where new companies could try their hand at bringing in audiences. And it did all this still without appreciable investment from government, corporate Bahamas, or major grants.

At the end of the 1990s, this changed. An endowment fund established by Winston Saunders—the Endowment for the Performing Arts (now the Charitable Arts Foundation)—whose initial purpose was to provide support for arts endeavours through The Bahamas matured. The first years of its existence saw it contribute considerably to the improvement of the Dundas. This enabled the theatre to secure the property with fencing and a wall, to erect a marquee to advertise coming shows, and to make various other critical improvements to the physical space.

Secure in its newfound source of revenue, the then board of the Dundas decided to do away with the repertory company. By 1999 the Repertory Season was also disbanded, and the Dundas entered the 2000s as a rental space only.

It became quickly apparent that rental income was not sufficient to cover the cost of the overhead of the theatre. The electricity bill alone was considerable, and without the consistent turnover of cash from repertory productions, those rents had to be raised until they became prohibitive. Eventually, the rehearsal hall behind the theatre was rented to a church, which helped meet the overhead costs. For about ten years, the Dundas was used sporadically by community groups seeking a place to hold a show. But in 2013, the arrangement with the church came to an end, and one year later, Ringplay Productions took over the management of the theatre.

In 2017, the mission of the theatre received an overhaul. It moved its focus away from training and job placement, and focussed more tightly on the performing arts, setting itself up explicitly as

… a community theatre dedicated to building community through culture, [providing] a home for vibrant performing arts companies, … committed to the development of the performing, visual, audiovisual, digital, and folk arts of The Bahamas.

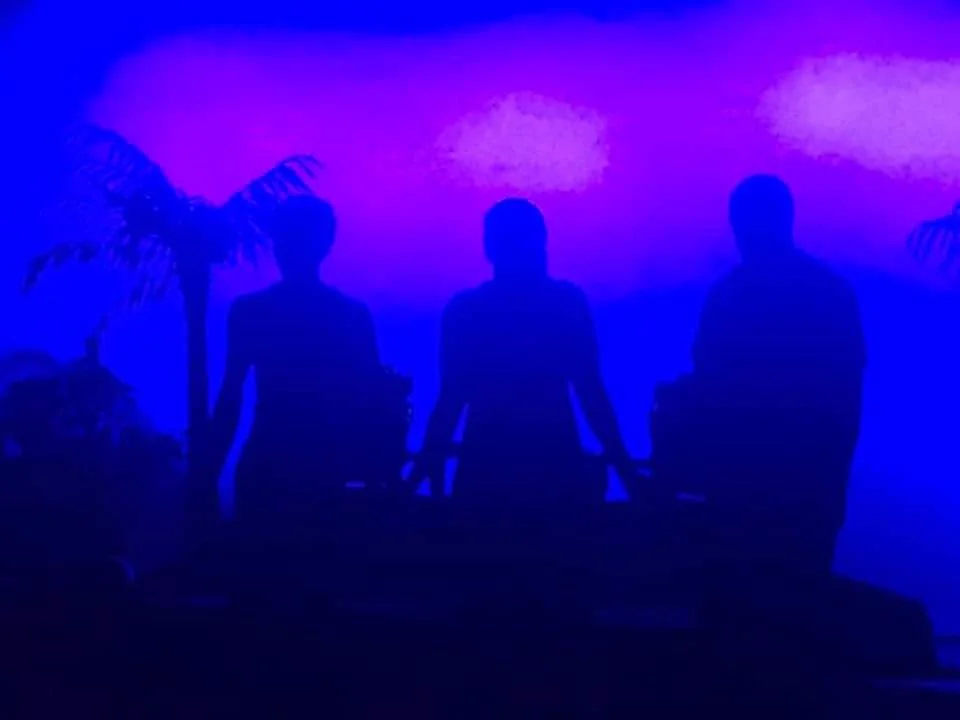

In 2019, the Dundas changed its memoranda of association to establish a twenty-first century board of directors and to restructure the Dundas as a self-sustaining community theatre. In January 2020, the Dundas started life with a new Board. At the helm, serving as Chair, was Philip A. Burrows, long-standing artistic director and one of the architects of the Dundas Repertory Season. With him were: Nicolette Bethel, Vice-Chair and co-founder of Shakespeare in Paradise; Delores Adderley, Treasurer and theatre manager; and Claudette Allens, longest serving Dundas Board Secretary. Other members of the Board included Dexter Fernander, Director of the Bahamas National Youth Choir; Adrian Archer, Musical Director for Christ Church Cathedral and founder of the Highgrove Singers; Sean Nottage, a long-standing actor on the stage, and others.

The first order of business was to raise the salaries of the theatre manager and the artistic director, who had been working since 2014 for a stipend of $1000 a month each. Under their leadership, the Dundas was now opening its doors year-round, and by the end of 2019, the theatre was bringing in enough revenue annually to support a raise. Their salaries were to double as of January 2020.

Various plans were created to help secure this goal. One of these was to keep the doors of the theatre open all year round. Another was to open the grounds on a daily basis as a kind of city park, a place in Palmdale where people could congregate, perhaps to eat lunch, maybe just to enjoy the ambience.

To achieve the first goal, Ringplay Productions kicked off its second full season of productions with Doubt in January 2020 and Diary of Souls in February. At the same time, the Dundas accepted a proposal from the Tin Ferl Collective to set up a food park on the premises. In February, Tin Ferl moved onto the Dundas grounds, and they had their opening events in March. In March, too, Ringplay Productions was working on its third production, the side-splitting comedy The Foreigner, designed to be the moneymaker of the season.

But then COVID arrived in Nassau.

Every kind of activity was stopped, not just the performing arts. This closure affected not only the productions that were in the works, but the brand-new arrangement that the Dundas had entered into with Tin Ferl. For the next two months, the theatre—indoors and out—was dark.

III.

But in May 2020, the country began to open. And this was Tin Ferl’s chance. Even though live performances were still prohibited, one of the permitted activities was drive-through/take-away food services, and this meant that the vendors in the collective could open.

And open they did!

The Tin Ferl Pop-Up Park flourished. What had begun as a collective of about ten vendors in the south-western corner of the Dundas grounds grew by leaps and bounds. That summer Tin Ferl was the place to be. And their business grew exponentially. As the country slowly reopened, people flocked to Mackey Street to hang out with the vendors, under the trees in the Dundas yard. And vendors also signed up to be a part of the action.

It was a great success, and the idea launched several new food services which would go from the park to brick-and-mortar locations. But the success was not purely due to the Tin Ferl model. This was a big part of it. But part of it also were the Dundas grounds themselves: a little oasis in the city. And part of it was also the continuing lockdown. For many months, the Tin Ferl Food Park was the only place where people could go to eat. Over the summer, the park quickly outgrew the vision that the Dundas had had for it. Instead of occupying the little-used south-western quadrant of the grounds, it took over the entire front of the Dundas yard. Vendors and cars parked all over the premises, both in front and in back of the theatre, and it was often very difficult for the theatre personnel to gain access. In addition, the Dundas allowed Tin Ferl to use the bathrooms of the theatre for their patrons, and at night their equipment was being stored in the foyer. The more Tin Ferl grew, the harder it became to imagine how the food park and the theatre could co-exist once the theatre was allowed to open again.

By the end of the summer of 2020, the Board began discussions with the collective to make plans for re-opening. Most important was ending the use of the foyer and the foyer bathrooms by the food park, as the re-opening of cinemas signalled the likelihood that theatres would soon be next (we had no idea that that permission would be delayed for another nine months!), and repairs now had to be carried out. Particularly important was confining the activity of the food park to the southern side of the property so that the theatre could be accessed by performers and patrons through the northern gate.

Also important was the question of rent. The discount provided to Tin Ferl had been designed to assist the collective to find its footing, but it was never intended to be a permanent arrangement. Nor had it been intended that Tin Ferl would be the only entity permitted to operate on the Dundas grounds. As a community theatre, the grounds as well as the buildings must be available to all the community. Now that the lockdown was coming to an end, the Dundas Board desired to provide space in its grounds for others to operate as well as Tin Ferl.

What was more, the rents offered to Tin Ferl at the beginning of the agreement were due to expire after the first year. After that time, to avoid allowing one group an unfair advantage over others, the rental being paid by Tin Ferl needed to be brought in line with that paid by other groups who rent the Dundas grounds. While a reduced rental was still offered to the food park for its weekly activities, the weekend use had to be reconsidered. Tin Ferl was offered the guaranteed use of the grounds at a discounted price one weekend per month, with the opportunity to book more weekends if there were no other bookings, but beyond that the Dundas calendar was cleared to allow other groups and companies a chance to use the space. Finally, it was stipulated that while reduced rents could always be offered to food vendors, entertainment was a different thing altogether. The Dundas is not in the business of subsidising its own competition. If Tin Ferl wanted to promote concerts and other performances, those events had to be booked and paid for through the regular channels, even if at a discounted rate.

These terms were laid on the table in October 2020, once it was clear that the lockdown restrictions were changing. The agreement with Tin Ferl was slated to expire in February 2021, and the Board was not interested in continuing the 2020 arrangement. The continued accommodation of Tin Ferl at the Dundas had to be compatible with the re-opening of the Dundas as a theatre.

Over the next four months, proposals went back and forth as the Dundas and Tin Ferl tried to find a compromise that would work for both parties. In the end, none could be reached, and the two parted ways.

So where are we now?

In May 2021, the Dundas reached an agreement with the Cultural Commune, aka Broadway at the Dundas, to establish its own food park on the premises. Unlike Tin Ferl, they did not flourish, and that agreement is at an end.

In August 2021, the Winston V. Saunders was deemed unrentable, as a year of inactivity caused the air conditioning units to fail. As of this writing, the main theatre remains non-functional.

In December 2021, after 18 months of being unable to function as a theatre, the Dundas welcomed the production of Competent Authority in the Philip A. Burrows Black Box.

At this point, the Dundas is engaged in planning and establishing a permanent vendor courtyard in the south-western quadrant of the Dundas grounds. It is also seeking to replace the old air-conditioning system in the Winston V. Saunders Theatre with a twenty-first century system. It also seeks to repair the perimeter wall to re-establish the security of the property.

The proposed courtyard will incorporate permanent booths for up to ten vendors, eating decks and parking for the park alone. It will be designed in such a way not to impede the access or use of the theatres proper, and it will be managed by the Dundas itself, rather than by a third party.

After this is developed, the next big project will be the creation and opening of the James Catalyn Amphitheatre. Fundraising activities will commence later this year.